Operational Excellence is Not Something New

There is a lot of content created around Operational Excellence and its companion disciplines – including; Leadership, Lean, Six-Sigma, Theory of Constraints, Project Management, and so on – which together comprise Operational Excellence (including the content produced by myself). But are all of these concepts as “new” as some would have you believe? Have they never been embraced or implemented in the past?

For your consideration;

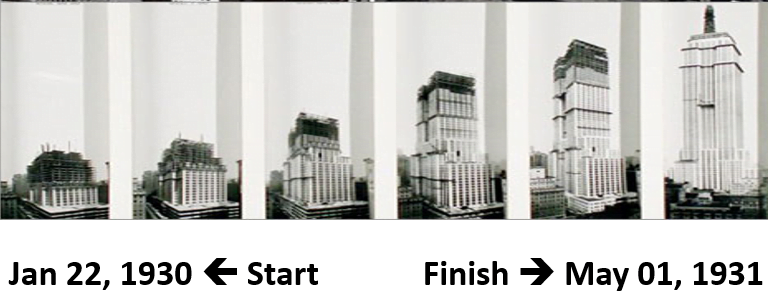

The date is January 22nd, 1930. The place is mid-town Manhattan. Right in the center of the lower portion of Manhattan Island. One of the most densely populated areas in the country at the time

It is in the early days of the Great Depression, and one of the most ambitious builds in modern history has started with the first shovel-full of dirt being dug from the ground – the Empire State Building. At the time, and for some time afterwards, it will be the tallest building in the world.

Construction started on March 17th, 1930 – a mere 54 days later.

And the ribbon cutting ceremony took place on May 1st, 1931.

From start to finish, it took only one year, three months, and nine days – 464 days in all to build – all 2,248,355sf of floor space and 1,224ft to the top floor.

If you consider the logistics, infrastructure, and circumstances surrounding the construction, it truly was an awesome feat. The Empire State Building consumed 57,000 tons of steel, which came from American Bridge (US Steel) in Pittsburg (400 miles away) and also Bethlehem Steel (100 miles away). It also consumed 200,000 cubic feet of Indiana Limestone (800 miles away). All of this material had to be transported by steam locomotive or ship, as there were no highways at the time. The material was stored and staged in New Jersey. Since the job site was the middle of Manhattan and there was no place to store a lot of material; every day, only that day’s worth of material was transported from New Jersey to the construction site.

On any given day, there were 3,500 workers at the job site. These many workers were required because the construction equipment available at the time was primitive and much of the construction was performed manually. To increase efficiency of the workforce, commissaries were built every few floors so the workers didn’t have to waste a lot of time walking someplace to take a break or to have lunch.

Certainly, health and safety were important to the workers and to the companies involved; but everyone lacked the experience (and imagination) as to the risks and the hazards. Also there was a lot of macho bravado among the workers which amplified the shunning of safety measures – and there was no Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) until President Richard Nixon would sign it into law on December 29th 1970. Even so, there were only five deaths on the construction site (with one person being hit by a truck). Tragic, yes. But amazing given the circumstances.

Compare this with the construction of the Freedom Tower that replaced the World Trade Center. After all of the legal and financial hurdles were overcome, construction started on June 23rd, 2006 with the excavation of the foundation. It finally opened on November 3rd, 2014 – a full 2,690 days to complete – with 3,501,274sf of floor space and 1,268ft to the top floor.

There are seventy-five years between the projects, the floor space of the Freedom Tower was only one-and-a-half times that of the Empire State Building, and it took almost six times as long to build.

Or think about other construction projects in contemporary times which have spun out of control such as; the new Berlin Brandenburg Airport (originally to cost $700-million and open in 2011, now over $6-billion and still not open), or the construction projects that the United States Veteran’s Administration that have turned into fiascos (in excess of 100% over-budget and three-years late, so far) – the list goes on and on.

So when I think back about the story of the Empire State Building; when I think about the all of the companies and all the workers that were involved in the project, when I think about the supply chain and the coordination that was required, when I think about the logistics necessary – I think about Operational Excellence and the High-Performance Organization.

Then consider the production of equipment during World War II when, at the peak production year of 1943, the United States produced (as just a small example); 1,238 “Liberty” ships (over three per day), 16,005 Landing vessels (44 per day), 9,393 4-Engine Bombers (26 per day), 21,743 Single-Engine Fighters (60 per day), and 29,497 Tanks (80 per day). And not just the actual manufacturing of all of the equipment, but the supply chain and logistics necessary to support the production.

Of course, the industrial world of the Twenty-First Century certainly out-produces the world as it was in the 1940’s. But that is not what I find remarkable. What I do find remarkable is the pace of the increase in production over a compressed period of time and all that had to be dreamt-up and put in place to support that pace.

So, when I think about the rapid scaling and transformation of heavy industry in the United States (GDP doubled between 1940 and 1943), when I think about the compressed cycle-times (from thinking about the product to its being manufactured), when I think about the supply-chains and logistics necessary for the raw materials to get to manufacturing and the final product to get to the field, when I think about all of the people involved – I think about Operational Excellence and the High-Performance Organization.

The motivation driving the Empire State Building was commercial, and the motivation driving the industrialization in the early 1940’s was certainly national, but that only demonstrates that operational excellence and being a high-performance organization transcends the source of motivation being either private or public.

Maybe Operational Excellence is not so modern a concept as some would have you believe. Certainly, its origin predates Toyota and the Toyota Production System and all of the other gurus who have dreamt-up and encapsulated the various methodologies over the past few decades. So what might be the real differentiator between all of these methods and tools and Operational Excellence and becoming a High-Performance Organization?

I would offer two suggestions:

Clarity of Purpose: Whenever the human endeavor has achieved greatness, the objectives have been crystal clear throughout the entire organization. Everyone knew what the goal was. The people saw the work and the work saw the people. And it is no coincidence that with clarity comes simplicity – complexity kills.

Minimizing and Stabilizing Priorities: If everything is a priority, then nothing is a priority – it is important to know what is important. Don’t spread your efforts more thinly than you can engage with efficiency and effectiveness. Set the priorities early and rally your resources accordingly. Once the priorities are set, resist shifting them. Sure, you need to have the flexibility to re-prioritize as changes in circumstances might dictate, but make sure to set the bar for re prioritization is set very high – for instance; because there are real threats to the successful realization of the goal, or perhaps because there are threats that would render meaningless the realization of the goal.

These two leadership traits – combined with a mastering of the methodologies and tools in support of strategy execution – will more likely than not lead to their existing Operational Excellence in your processes and systems, creating a State of Readiness across your value-chain, and offering the opportunity for your company to become the High-Performance Organization.

Joseph Paris is an entrepreneur with extensive international experience. He is the Chairman of the XONITEK Group of Companies, an international management consultancy firm he founded in 1985; and the Founder of the Operational Excellence Society, a “Think Tank” dedicated to serving those interested in the disciplines of Operational Excellence.

In addition, Paris serves on the Advisory Board of the System Science and Industrial Engineering Department at Binghamton University and on the Process Industries Division at the IIE. He is also on the Editorial Board of the Lean Management Journal and a sought-after speaker, guest lecturer and writer.

Connect with Paris on LinkedIn